Behold the Great Outdoorsman, bravely stalking the north bush for his quarry. He has come to observe, up-close and in the unmitigated wild, the ferocious Alaskan brown bear. See him push from his mind the niggling fact that in his fraught quest he carries neither rifle nor shotgun nor bear spray—indeed, is armed with nothing more protective than a spray-can of mosquito repellent—and that his most technical piece of bear-stalking apparel is a pair of caution-light-yellow clamming boots, which at this moment are being sucked from his feet by a vengeful tidal goop. Before him, Alaska is a broad baize beneath weeping clouds. He lifts his powerful and overpriced binoculars to his eyes and scans the horizon.

There, in the distance! A brown hulk squats, unmoving, on the tidal flat. Even from here he can see its dark ursine mass rippling with potential energy, waiting for the moment to burst toward his group with merciless velocity.

"Mud bear," dismisses his guide, walking onward.

Ah.

Truth to tell, the Great Outdoorsman is a bit jumpy, and also is growing near-sighted. He is not feeling altogether great at the moment. He has come to the McNeil River State Game Sanctuary to see why, each summer, this place claims the crown as the beariest place on earth. But the rain has made him shivery, and he thinks he has forgotten his pocketknife at home.

For 20 years he has lived in Seattle, which not long ago felt like a big mountain town, but now is the fastest-growing metropolis in the nation. His life mirrors that of his city, further removed from nature by the day. The three-hour rush hours that lead out of town discourage him. So do the 200 cars he sometimes finds at the trailhead. He feels stuck in the traffic jam of the Anthropocene. Instead, he spends long hours at his desk, and on the telephone, trying to do big things, and to be big.

Sometimes the Great Outdoorsman—my better, former self—stops striving long enough to wonder, Is this all there is? Must we spend our days trying to control the world around us, even as things spin out of control? When those questions become too much, he knows it's time to escape from behind the bars of his cellphone and get beyond the reach of other humans. Way out here, in places like this, he likes to think, a person can better see how the world fits together, and perhaps see where he, too, fits in.

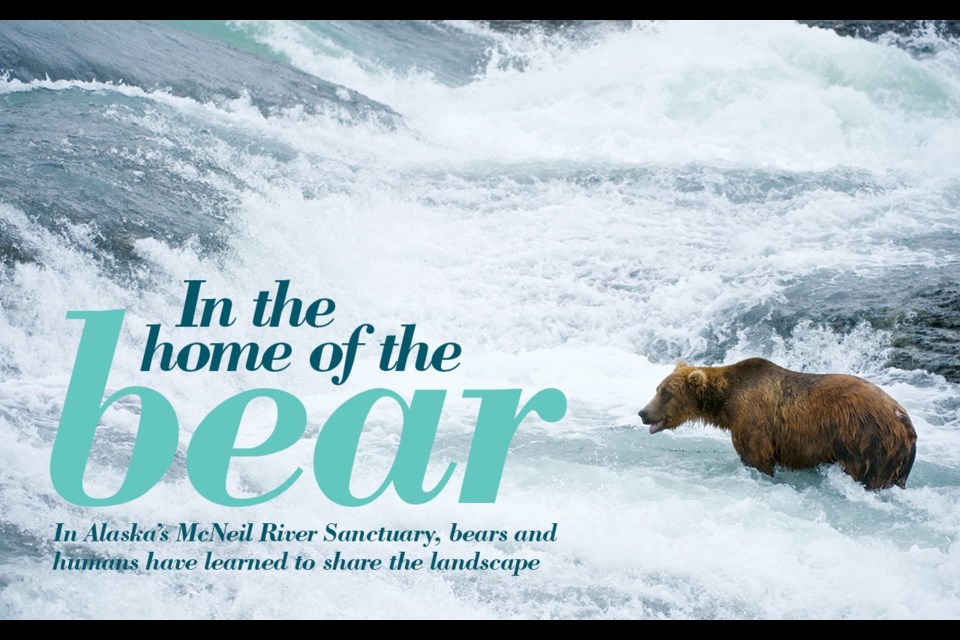

'That's more bears than there are in France!'

You have seen the poster hanging in the harshly lit purgatory of a dentist's office or strip-mall DMV: a bear standing at the top of a foamy cataract about to devour a leaping salmon. Beneath the bear, a single sentiment: PERSISTENCE. These photographs are mostly taken at Brooks Camp of southwest Alaska's Katmai National Park where, on a busy day, a squadron of floatplanes shuttle hundreds of tourists to gawk at a handful of bears on the river. It's impressive, and also crowded.

Northeast of Katmai at McNeil River, by contrast, 75 bears have shared the falls of the river. On the same day. At once. "That's more bears than there are in France!" Larry Aumiller, a former manager of the sanctuary, said upon witnessing the scene in 2011. When the salmon are running thickest in the McNeil River in mid-July, it's normal to watch 40 bears fish together.

The numbers are all the more remarkable when one considers that perhaps only 1,800 grizzly bears roam the Lower 48 today. They occupy about two per cent of their historic range. In the Greater Yellowstone Area, lawyers sue over whether one grizzly per 58 or so square miles is enough to consider the bears recovered. Alaska, on the other hand, has 32,000 brown bears, which are basically grizzlies that enjoy coastal living. Their numbers may be most dense of all on the Alaska Peninsula of southwest Alaska. Here, on average, there's roughly one brown bear every square mile.

While nearby Kodiak Island likes to brag that it's home to the biggest browns on earth, the Alaska Peninsula grows 'em just as big—up to 680 kilograms for the truly colossal males. To conjure the falls at McNeil in midsummer, imagine 40 bears standing in a space a bit larger than half the size of a football field, with each bear weighing as much as two NFL defensive tackles. It's the largest seasonal gathering of the biggest brown bears on earth.

These bears don't live behind a zoo's high walls. They are free-range, completely wild, and they largely go where they want. Here, a bear will catch a salmon, step out of the river and eat its dinner, just a fish-stick toss away from the unfenced, ground-level pad where stunned humans sit and watch. A few years ago, an IMAX cameraman found himself frustrated: The bears were too close for his lens to focus on.

"This place is not a park," Tom Griffin, who has worked at the sanctuary for more than 18 years and managed it since 2010, says. "With the exception of human safety, that world out there belongs to the bears. When we leave camp every day, we have to control our behavior."

Unlike Brooks Camp, access to the McNeil Sanctuary is strictly limited, to only 10 visitors at once, four days at a time, 200 visitors a season. To come here, you must win the lottery, literally: There's a drawing each spring for spots, with preference given to Alaskan residents. Finally, a good reason to persist for hours at the Nome DMV.

'Perfect brown bear country'

In June, having won a coveted out-of-state lottery spot, I stand on a dock in Homer as a young pilot named Jimmy stows my duffel in his ancient, reliable de Havilland Otter. Two couples arrive to share the ride. Soon we're up and arrowing west toward the Alaska Peninsula, leaving behind house and highway and the halibut charters that split the waters of Cook Inlet. Clouds smudge the horizon like a finger run across a chalk line. The clouds push the plane low. None of this seems to faze Jimmy, who navigates by iPad, texting as he flies. Having stowed my technology for the next several days, I look out the porthole, though, and feel a geographic vertigo set in. Past and future erased, all that remains is a not-unpleasant feeling of going—that, and the sea below, the colour of flea-market jade.

In time, a rocky island appears, then another, followed by steep headlands and small bays that reach back into a delirium of grass and alder, a world painted in approximately 26 shades of green. Like eyes adjusting to the dark, it takes a few seconds to see what's not there, which is nearly anything that says humankind. I do spy a brown dot among the green. Then a second one. Jimmy sets the floatplane down on the high tide and cuts the engine. "I saw 10," he says, unbuckling, with the matter-of-factness that steered us here.

The human footprint at McNeil consists of a clutch of old cabins and tent pads huddled at one end of a parenthesis of sand and driftwood. On one side of the sand is a tidal cove. On the other, beyond Kamishak Bay and Cook Inlet, lies the North Pacific. Encircling camp is a low hedge of Sitka alder. This hedge isn't so high that I can't look across it and watch bears munching grass. As barricades go, the hedge is risible. Except that it works, mostly. This small patch belongs to humans. The rest of the 518-square-kilometre sanctuary is for the bears.

We unload the floatplanes and haul gear down the beach, led by Beth Rosenberg, the sanctuary's assistant manager. Rosenberg is a friendly, caffeinated presence with dark hair and cheeks ripened by the brisk Alaskan summer. Before she's friendly, though, she's a martinet. She orders our group of 10 to purge gear immediately of anything that has an odour. Food, toothpaste, mouthwash, deodorant: all marched into the cook shack instead of the tents.

Rosenberg chases this order with more camp rules, simple and inviolable: When you walk to the outhouse, which sits among tall grass some distance away—clap. Do not walk alone outside the hedge. Do not leave the hedge without permission. She doesn't have to ask twice. Bears are everywhere. Bears clamming on the mudflats. Bear cubs rough-housing on the beach. A mother bear eating sea pea, two feet from the hedge. Where there are no bears, there are signs of them: Inside the cook shack is a cast of a paw print. It is the size of a garden rake. Chew marks scar the door of the wood-fired sauna down the path from my tent.

After we pitch camp, Rosenberg guides several of us outside the perimeter to a creek to fill jerry cans of water. Heavy whorls depress the tall grass around us, as if an engine block had recently arisen from a nap. I've never been so attuned to every sough of wind, every rustle of leaf. I take stock of my situation: Four hours earlier I was a white, middle-aged, white-collar American male. Statistically speaking, I straddled the world. Now, I'm on the menu—in theory, anyway. The skin prickles as if in the moment before the lightning strikes. Nothing focuses the mind like the realization that you no longer stand atop the food chain. It is exhausting, and exhilarating. Back at camp I unzip my tent flap and send a bank vole skittering for cover. "I feel you," I say. At bedtime I give myself a standing "O" on the walk to the privy, then lie awake and listen to a golden-crowned sparrow sing its three-note song: Oh poor me, oh poor me.

Sleep that night takes the long road around the mountain.

"It's a Kamishak-y day—50 shades of grey," Rosenberg greets us the next morning in the cook shack. The one-room shack serves as our kitchen and living room. It holds a few tables, a crackling woodstove and shelves that sag with field guides, all of it secured behind a heavy door. On another shelf sit a dozen air horns, and a note: "Toot twice if a bear in camp."

We bundle up and walk outside, single-file, into perfect brown bear country. Low tidal flats yield to sedge prairie, which gives way to low, humping hills bearded with low alder. On the horizon stands a single poplar tree. The air smells of grass and mud and bear shit—a green, horsey smell of ripe decay and the beginnings of the world. Rosenberg leads the way. She walks with the deliberation of someone entering the house of a neighbor who she's not sure is home. "Hey, bear," she says, in a tone that's almost conversational. "Hey, bear." Slung over her shoulder, and also over the shoulder of state research biologist Dave Saalfeld, at the rear of the group, is a Remington Model 870 shotgun filled with slugs.

The guns remind me of the letter that arrived in the mail with notice of my lottery win. The letter encouraged visitors to bring neither pepper spray nor weapons to the sanctuary, invoking its excellent safety record. No one has been injured or killed by a bear in more than four decades since the permit system began, and no bears killed by visitors. The implication is clear: Who are you to disturb the universe by being the first?

We splash across Mikfik Creek, a salmon stream that by late June is a trickle. Rosenberg halts mid-stream. On a small rise about 55 metres away, half-hidden among the tall grass, is a brown hump to loosen a hiker's bowels. The sanctuary's managers know more than 100 bears by sight that return here year after year. But Rosenberg doesn't recognize this one. Ankle-deep in the water, we pause and watch the stranger.

"Let's just walk like this—in a blob is great," she says after a few moments.

We splash forward.

The bear comes more into view. He's an adult male, his great head resting on his great paws. He raises his head. Considers the air. Yawns.

Boredom! I think. This seems propitious.

It isn't propitious. "Animal signals are not the same as human signals," Rosenberg says. "A yawn usually signals mild concern."

Our blob pauses again. The bear lowers his head. We splash forward, slowly. He raises his head. We stop. So it goes, with permission, until we have passed him, a humbling Simon Says with North America's apex predator.

Rosenberg walks us farther upstream on what appear to be hiking trails. They're not hiking trails. Look closer. "These are all bear trails," she says. "We just happen to use 'em." Sometimes, the roads are so worn into the earth from decades of use we walk nearly knee-deep to the surrounding land. Turf runs down the middle of the paths where the gap-legged bruins saunter: Bear highways complete with bear medians. Bald eagles lift, pterodactyl-like, from a cliff above our heads.

In time, Mikfik Creek enters the hills. There we sit on a grassy knoll above the trickle. It is the waning days of salmon-fishing for the year on Mikfik. An aging bear named Rocky with a necklace of scars lies on a patch of grass beside the creek. He watches a female named Queen Bee fish at a small spillover where the red salmon bunch as they try to make it upstream to spawn and perish.

Adult females like Queen Bee may become receptive to a male's advances for only a short period in the late spring. Rocky is biding his time. (Managers use names here for bears instead of numbers because it makes it easier to remember the scores that return annually, not because they consider them pets. When an animal has a bite-force greater than an African lion, "Hot Lips" isn't an endearment.)

Another big male enters, stage right. He's the colour of a $4 chocolate bar. Rocky stands and walks almost wearily toward Queen Bee, to show his ownership. The newcomer cuts high on the slope above the creek to approach Queen Bee from another direction. Rocky checks him coming around a willow. It's the age-old drama in a different playhouse—love and war and what's for dinner.

A brown bear will never earn the word "graceful." Consider Rocky: His gait is pigeon-toed. His back is hunched with muscles for grubbing roots and grabbing rodents from their dens. From a distance his face seems as wide and flat as a hubcap. When he walks, his rear legs saw, arthritically, resisting forward motion and one another—one-two, one-two. Watching Rocky lumber toward his rival, my abiding impression is of an articulated bus coming into service.

This is deceptive. The final regret to pass through a human brain is having misjudged the speed and agility of a brown bear. At track distances, an adult brown bear can run down Secretariat.

While I'm mulling the velocity of large carnivores, Queen Bee suddenly appears on the hill just 40 yards away from where we sit. The dark suitor follows immediately behind her. She lets him draw close. He stands and mounts her, biting her behind the right ear and holding tight. For 45 minutes. We make embarrassed jokes, but still take snapshots. Rocky, outflanked, lies down beside the stream, his head on his folded paws.

He may yet get his shot at immortality. A female normally mates with a few males in June and then, in a practice called delayed implantation, holds the blastocysts for several months in her uterine horn. If she's sufficiently fed in summer, the pregnancies take hold in the fall. In January, she will give birth in the den to possibly several cubs—pink, hairless, one pound, premature—who will suckle for months in hibernation. They may all have different fathers.

One day as we walk to McNeil Falls with Griffin, the sanctuary's manager, we meet a nougat-colored bear named Quinoa and her yearling. We pause at a respectful distance for a few minutes, then Quinoa lets us pass within about 25 feet of the two—close enough to hear her tear sedge from the earth. Afterward, Griffin turns to us. "What we just did," he says, "you would not do almost anywhere else on earth."

At McNeil, though, humans have found a way to abide with the bears. It's been a crooked journey. The territorial government of Alaska first recognized the unique congregations of bears here and closed off the McNeil drainage to hunting in 1955. A dozen years later, the state legislature created the sanctuary, with a far-sighted mandate to place the welfare of the bears first and human appreciation and research second. As word got out, flocks of people showed up to see the bears, until the falls were overrun with people, Jeff Fair writes in In Wild Trust, his excellent 2017 book about the sanctuary.

Confrontations sometimes led to the killing of bears, until area biologist Jim Faro, in 1973, successfully lobbied for a permit program to limit the number of visitors.

The longtime sanctuary manager under Faro, Larry Aumiller, spent three decades studying how humans could live in harmony with Ursus arctos on the landscape. Perhaps no one in modern history had ever done anything quite like it. Aumiller made rookie mistakes—walking heedlessly through thick brush, staying all night at the falls, alone ("Bears own the night," he told Fair)—but over time, he learned how humans and bears could reside together.

And what works? First of all, restraint—not bulling into the landscape. Bears don't like surprises. Moving slow and being predictable are good starts. That's why humans walk the same trails, about the same times every day, and in the same group size. Over decades of such long and careful practice, the bears here have learned to see humans as another presence on the landscape — neither the source of a meal, nor the cause of pain or fear. They are "neutrally habituated," in the argot of this place.

Watching Quinoa and her offspring, it occurs to this still-fidgety Outdoorsman that, should mama grow angry, she would cover the ground that separates us before Griffin could unshoulder his Remington. But Quinoa never looks up, and never stops eating. She's aware of us. But as long as we remain predictable, and respectful, she remains comfortable.

And if the managers do need to alter a bear's behaviour—to keep a bear outside of that hedge, say—they rarely need anything as persuasive as that shotgun, or even a firecracker. As little as a sharply spoken word, or a shake of a saucepan filled with rocks, is almost always enough to dissuade a neutrally habituated bear.

All this helps create a memorable human experience. "When bears are comfortable, they stick around and we can watch them," Aumiller told author Fair. "And when they are comfortable, unstressed, they are safer in general to be around. So, it turns out, safety leads also to proximity."

Unfortunately, McNeil remains the exception. "Don't try this at home," Griffin reminds us one day after another close encounter. When he's not at McNeil—for a hike near Anchorage, say — and he thinks a bear is near, even Griffin heads in the other direction. Almost everywhere else, the ability for humans and bears to move easily among each other has been lost. What is different at McNeil is that humans don't try to dominate. We listen. We adjust. We find out how it all fits together, and where we fit in. "Here we learn that we can live among the great bears," Fair writes. "Here we learn the human behaviours that allow this." In more than 70,000 encounters with bears over 30 years at McNeil, Aumiller was charged just 14 times—one-fiftieth of one per cent of meetings—and not one of them resulted in injury. All those bears, it turns out, were newcomers to McNeil.

There's one more reason McNeil works: There's still enough elbow room here, and food, for a bear to be a bear. We haven't diced up the land, dammed the river, paved the mudflat, or shot the residents. At McNeil there are clams and young sedges in spring, when other food is scarce. The reds run up Mikfik in early June, followed by the main course, the chum salmon, in late June and July. The feast concludes with crowberries, low-bush cranberries and blueberries for dessert in late summer and fall. The McNeil Sanctuary remains an intact, groaning buffet table. And it brings in the crowds. As if to underscore that point, one morning even before we head out, we can count 12 bears from the door of the cook shack—bears clamming, bears scanning the tide for fish, bears gorging on sedge. "It's habitat, with a capital H," says Rosenberg.

Something good is happening to me. My once-fearful "Hey, bear!" has turned interrogative. I pull on the fleece and slickers, anxious to get out among them.

The season of plenty

The first bloom of the wild iris coincides each year with the arrival of McNeil River's chum salmon run. Whether the brown bears of the Alaska Peninsula are observant botanists remains an open question, but somehow they know to come. On our second morning we follow Griffin past bouquets of iris and head into the spitting rain. Walking at the speed of a funeral cortege, we cross the wide sedge flats, pass beneath bluffs and their hanging gardens of Kamchatka rhododendron, then angle across tundra sprinkled with heather flowers.

We hear the McNeil River before we see it. The falls consist of about 100 yards of sluice-y whitewater located about one mile upstream of where the river spills into the ocean. The falls are neither wide nor steep. They are obstacle enough, though, to give pause to tens of thousands of chum salmon that each year try to return to the hills, and the waters of their birth. Chum salmon are poor jumpers, so the fish gather themselves at the base of the rapids to think things over before tossing themselves into the rapids. The bears are waiting.

It's quite a thing to breast a green rise to the sound of smashing water and come upon a dozen bears, or three dozen, standing in a cataract, fishing. Some point downstream. Some point upstream. Some stare into the cappuccino foam of eddies as if all the answers are held there. Still others "snorkel," shoving their snouts into deep pools and then diving, rumps skyward, like fat children diving for pennies. Sated bears catnap on rocks in the river. Every few minutes a new bear materializes from the alder and descends to join the group.

At two gravel pads—room-sized, unfenced, just a few feet above the river—Griffin hands out more rules: Do not leave the pads. Do not stand quickly. Do not move between the pads without permission. We settle in on folding chairs to watch a show with more players than a soap opera. A bear named Aardvark charges Hot Lips over his prime fishing spot. They rise and slam into one another. They bite each other on the neck, hard. The fight is over quickly. Hot Lips reluctantly backs away. Aardvark takes the spot and soon has a fish.

Early in the salmon run on the big river is the time for sorting out the pecking order. In nature, though, fighting is expensive. Bears avoid it if they can. Instead, they try to intimidate. They swagger. They huff and salivate. On bowed legs, they walk slowly, stiffly toward an adversary—cowboy in the front, sumo in the rear—to see who veers first. Bears that don't want any trouble move crab-wise around one another with the no-sudden-movements of gunslingers who just rode in for a sarsaparilla. Ironically, says Griffin, by the time 40 or more bears fish together later in July, there will be fewer scuffles.

At high season, with enough fish running for everyone, the bears will gorge and grow fat. During the peak of such salmon runs a coastal brown bear may eat 41 kg of salmon per day and pack on one to three kg of fat. An adult male like Rocky might pack on 25 to 30 per cent of his body weight and waddle away to a winter's den weighing 600 kg. When fish are most plentiful, bears will "high-grade"—eating only fatty skin or brains. Some McNeil bears get so full and so selective, they've been known to hold a salmon in their mouths and gum it for eggs, or drop a male fish without taking a bite, writes biologist Thomas Bledsoe in his book about McNeil, Brown Bear Summer.

As we sit and watch, a big male comes up the bank with a wriggling hunk of sashimi and settles into the tall grass within seven metres of the pad. His muzzle is smeared with blood. We stare at each other. I feel an almost overpowering urge to reach out and touch him. I want to connect with something so wild, of such terrible power and beauty. I have felt that feeling once before, exiting a helicopter, when I felt an overwhelming desire to put my hand to the spinning rotor blades.

The result would be roughly the same.

I don't reach for the bear.

This is another of McNeil's lessons. Let nature draw near, if it wants to. Close your eyes and let the moment burn behind your eyelids. Do not, however, mistake proximity for mystical connection. Do that, and you'll end up the subject of a Werner Herzog film. People will remember you, but only as a cautionary tale.

The barometer plunges. Fifty-km-an-hour winds sweep the peninsula, driving the kind of rain that finds the weak spots in your waders. Each morning we leave the camaraderie of the woodstove and venture into the gale, past a yellowing note tacked to the shack's door: "Bad weather always looks worse through the window."

The note knows. We sit at the falls in our lawn chairs for hours, soaked but transfixed. More bears arrive by the day. In the air is an odour that recalls an old bathmat—eau de wet fur. How many bears have I seen? Counting seems irrelevant now. Counting is what the old me thought was important. Instead, I try to pay attention, reminded of Simone Weil. "Attention, taken to its highest degree, is the same thing as prayer," Weil said. "It presupposes faith and love."

I watch a bear called Revlon install himself in a Class III rapid. His legs could be the pilings of the Triborough Bridge. He stares at the water with mineral patience. Finally he lunges, pins a 50-centimetre chum to the bottom. He eats it where he stands. A female named Ivory Girl with gorgeous, bone-coloured meathooks works her way among the males, begging for food. I watch a lone wolf—soaked, yellow-eyed—appear on the far shore, slinking among the bears and sneaking scraps.

One afternoon as we sit at the falls with Rosenberg while the day's variety show plays out and the wind howls its approval, one bear begins to chase another over some beary slight. The first bear races out of the water, headed for the near shore. In about two seconds, he's up on the bank, the other bear in fevered pursuit—right toward us.

My amygdala is throwing off sparks. Immediately I'm on my feet, breaking the rule. If there were time, I would break more of the rules. But there's not time. The lead bear is now six metres away. The electric prickle returns and races up the spine and across the scalp, the feel of lightning about to strike. Everything slows. The world shrinks until it is seen through a pinhole camera. Einstein needn't have looked to the heavens to contemplate space-time collapse. He could have stood before a charging bear.

Rosenberg stands slowly. The lead bear is close enough now for us to see pearls of slobber arc from his mouth. Rosenberg doesn't retreat. Instead, she steps toward the advancing bears. "Hey," she says. The word is as short and sharp as two stones clacked together.

The lead bear lifts his head and looks directly at Rosenberg. The look isn't angry. Instead, it's one of surprise, and recognition. Oh, the look says. Yeah. Then, without breaking stride, the bear pivots left, toward the tall grass.

Exit, pursued by a bear.

'A brush against nature'

Weeks later, back in Seattle, the Great Outdoorsman tells himself that, in the moment when the bears charged, he felt privileged to witness such a thing. This, of course, is revisionist hooey. When a Hyundai's worth of meat is bearing down, "privileged" doesn't make the emotional Top 10.

Only upon reflecting in Wordsworthian tranquility does he think, Yes, precisely, that's exactly what I needed: not any great lessons, but simply to brush against nature, where it still exists in all its humming electric-dynamo bigness. And to be reminded of my smallness, and how good it feels to revel in this smallness, and find again where I fit. And then to come home, thinking small again.

Thus re-baptized, the Great Outdoorsman resolves to get outside again soon, traffic or not. Next time, he swears he will remember his pocketknife.

This story originally appeared in the Dec. 25, 2017 issue of High Country News.